The livelihoods and cultural identity of Vezo people in southwest Madagascar are intimately intertwined with the marine environment. Vezo livelihoods, however, are increasingly threatened by overfishing and mangrove deforestation, largely driven by demand from outside markets. Climate change is also having an impact, creating inconsistent wind patterns and rough seas too dangerous for fishing. Blue Ventures has been working with partners to pioneer viable alternatives to fishing to support alternative livelihoods, alleviating pressure on fisheries while gaining a new source of sustainable income through lomotse (seaweed) and zanga (sea cucumber) farming.

This series of aquaculture profiles, written by Angelina Skowronski, explores the opportunities for livelihood diversification and capacity building through the eyes and words of Vezo fishers themselves.

Mikarakara Kirise. She takes care of things. Herself, two of her family members’ children aged 18 and 21, her seaweed farm, and her future.

“Miarakara zaho (I take care of things). I can afford to buy clothes and food now”“Miarakara zaho (I take care of things). I can afford to buy clothes and food now,” she says, while kneeling next to her thatched home, just steps from the sand’s damp high tide mark on Nosy Tsolike’s beach. From her home, she can see her seaweed buoys, recycled Coca-Cola and Eau Vive (Madagascar’s ubiquitous bottled water brand) dancing in the swell.

She’s thin, which showcases the developed muscles in her forearms, proof that she’s not afraid of manual labor. Before becoming a seaweed farmer, she made limestone ash used for cement mix. The process to make limestone ash is labour-intensive, requiring hours of collecting shells, cutting mangroves, and burning the material into ash.

Life was difficult. It was hard manual labour, and I could barely afford to clothe or feed myself,” frowns Kirise.

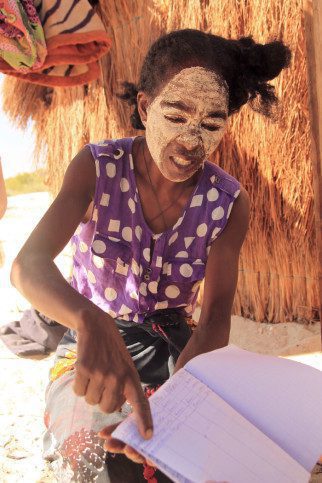

Tabaky, a facial cream made from wood and worn by Vezo women, covers her face as if applied by a professional. Her frown turns to a smile, and the dried tabaky cracks and peels at her laugh lines, exposing the exfoliated skin below.

Kirise is a divorcée living in a small village along the Bay of Assassins, so her need to mikarakara is a result of being a single woman and her own personal motivation. In 2014, Tafita, a friend of Kirise, introduced her to seaweed farming.

[Tweet “Everyone would say, ‘your livelihood is too hard on you.’ But I didn’t know how else to get by. “]

“Everyone would say, ‘your livelihood is too hard on you.’ But I didn’t know how else to get by. Then Tafita showed me what to do; how to take care of the lines, and even loaned me the ropes and seaweed starts,” says Kirise. “Seaweed farming got me out of poverty, but if I wasn’t personally motivated, I would still be poor.”

Kirise recognises that her success is self-generated; that because the farm is her own and no one else’s, she must mikarakara. She must rely on herself to tend the lines when sea grass or rubbish is tangled, to make reparations, take count of what has been lost after storms and big tides, and to multiply, harvest, dry and transport the seaweed to Tampolove.

More than seaweed farming, she’s also learned how to plan for her future. Blue Ventures’ partnership with the Malagasy NGO CITE provides small business management training to the farmers. Farmers attend annual training sessions, which build money management, accounting and saving skills. Through CITE’s workshops, Kirise learned how to keep track of her income and expenses through the use of a cahier (notebook).

“Even if I don’t write down the expenses right away, I will do it in the evening. It’s never far from me,” she says.

She runs into her home and retrieves her cahier. The front cover of the cahier has the image of a goal net and football, one that a teacher would find in the rucksack of an elementary school student. Kirise’s fingers leaf through each page, showing her meticulous recordkeeping. It’s clear that she used a ruler to create perfect lines for columns titled: vola miditra (money in), vola miboake (money out), and ‘totaly’ (total).

She runs into her home and retrieves her cahier. The front cover of the cahier has the image of a goal net and football, one that a teacher would find in the rucksack of an elementary school student. Kirise’s fingers leaf through each page, showing her meticulous recordkeeping. It’s clear that she used a ruler to create perfect lines for columns titled: vola miditra (money in), vola miboake (money out), and ‘totaly’ (total).

Nanao fiantsira (sold salted fish) + 6,000 Ariary

Nividiana sakafo (bought food) – 2,300 Ariary

“I even help people who don’t know how to write. They come to me and I write down their expenses in their cahiers for them,” says Kirise, with a big smile and proud eyes framed by the beige-colored tabaky.

Because of her success, she’s been trying to encourage other community members to start seaweed farming.

“The community sees that I can now afford food and clothes, and that my life has changed. I’m treated with more respect here because seaweed farmers are given respect in the community,” she says with conviction. “I want others to experience this also and be successful.”

Kirise’s current success story comes at a cost of pervious hardships. Not just of poverty, but of loss. The divorce, she describes, came more as a product of fate rather than want.

She and her former husband tried to start a family during their 16-year marriage. Whenever she tried to have children, she would feel pains. The local medical center told her she need to go to Toliara to see the doctors there and perhaps have an operation. She was told that carrying a child could be fatal otherwise. At the time Kirise and her husband did not have the money or the means to make the 13-hour journey to Toliara, so she accepted that motherhood was never meant to be.

“I ended the marriage so that he could find someone to have children with,” releases Kirise, the tabaky scales falling from her furrowed brow.

They separated. Her former husband remarried and had children with his new wife.

“So now I must mikarakara for myself and my future.”“I told him that I could take care of his children, but he told me they already have a mother who can take care of them,” she says, the resurfaced memory cracks her wise voice. “So now I must mikarakara for myself and my future.”

This is the fifth in a series of aquaculture profiles, written and photographed by Angelina Skowronski, which explore the opportunities for livelihood diversification and capacity building through the eyes and words of Vezo fishers themselves.

You can find out more about our aquaculture work on our website. We would like to thank our partners for their commitment and expertise without which such projects would not be possible.